End of the road looms for the Philippines’ jeepneys.

Almer Lacorte earns about $20 a day driving a jeepney between Manila’s Santa Ana district and Rizal Park, taking 20 passengers at a time in his vehicle on facing bench seats.

With their chrome finish and hand-painted exteriors, jeepneys provide distinctive flash and colour to Manila’s streets, and are a staple of the Philippine capital’s woefully overtaxed transport system — short-hop vehicles that get commuters between their homes and buses or trains.

Jeepneys get their names from the vehicles US troops left behind after the second world war, which local entrepreneurs refitted with passenger cabins and painted slogans such as “King of the Road”, and are an indelible a part of Philippine folklore.

But now President Rodrigo Duterte’s government is launching a long-delayed drive to remove older jeepneys such as Mr Lacorte’s from the road and replace them with lower-emission ones, including cleaner diesel versions or electric-powered “e-jeepneys”. It has set a target of removing all jeepneys 15 years or older from the roads by 2020.

The government says jeepneys poison the air and contribute to traffic gridlock in Manila, one of the world’s most congested cities, according to the Google-owned mapping and navigation app Waze.

“The one reason why modernisation was not really pushed during past administrations, for more than 50 years, is because they [drivers] are a political force,” said Thomas Orbos, an official in the Philippine Department of Transportation. “The jeepney sector alone is a political force to reckon with, and we’ve taken it on headfirst, and we know what we’re up against.”

The Duterte administration, in proceeding with the upgrade, is portraying itself as championing the needs of millions of working Filipinos who spend hours stuck in traffic every day, against what it says are vested interests. Poor public transport was one of several popular grievances on which the Philippine leader campaigned to win the presidency two years ago.

“Son of a bitch, suffer hardship and hunger, I don’t care,” Mr Duterte said in a characteristically aggressive speech last year after jeepney drivers who opposed the changes staged a transport strike. He also threatened to “drag away” recalcitrant drivers from their vehicles.

But jeepney drivers, most of whom subsist on modest wages, and operators — small businesses that typically own one or two vehicles — have described the upgrade as part of a war by the administration on the urban poor.

“The president has contempt for poor people asserting their rights, and jeepney drivers are a challenge for him,” said George San Mateo, head of Piston, a transport workers’ group who were involved in organising a strike last year. “This programme will push small operators out of business.”

The Ibon Foundation, a public policy think-tank, has urged the Philippine government to undertake jeepney modernisation without jeopardising drivers’ livelihood or commuters’ access to them as a mode of transport, as part of a plan that takes all interests into account.

“We have too many cars, but we don’t have enough roads,” said Rosario Bella Guzman, an Ibon director. “The government is looking at the jeepney as the culprit.”

Mr Orbos, the government official, denied jeepney drivers were being scapegoated. “They are not being singled out,” he said.

According to the transportation department, there are 178,000 jeepneys in the Philippines, 90 per cent of which are at least 15 years old.

The government’s plan is to cut the number of routes, and of vehicles vying for business. Fleet operators will be offered subsidised loans to buy new jeepneys, and drivers moved to a standard monthly salary and benefits, rather than hand-to-mouth wages.

Manila’s two main family-owned producers of jeepneys say they are ready for the switch.

Sarao Motors has produced a boxy, modern “e-jeepney” that resembles a small bus.

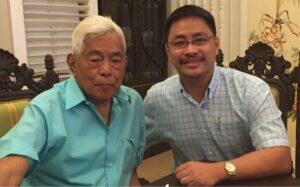

Francisco Motors, which has been making jeepneys since 1947, is showing its own demonstration electric jeepney in Manila’s Rizal Park, painted in classic multi-hued style, with clenched-fist logos — Mr Duterte’s signature gesture — on the front.

“If you take away the classic design of the jeepney, it is like taking away part of our identity as Filipinos,” said Elmer Francisco, the company’s chief executive. “Our president would like this to be preserved.”

Mr Lacorte, the jeepney driver, voices doubts that either he or his passengers will be able to make the shift. Most jeepney passengers are poor people whose main concern is to get from point to point at the cheapest price, usually to transport goods or produce.

“We don’t want the electric type, because they won’t work here, especially on rainy days,” he said.

Additional reporting by Guill Ramos